I mean, all the CA systems I’ve worked with in the past relied on neighborhood rules (like in Conway’s Game of Life). Actually, this was the first time I experimented with such a system. A few tweaks (not to the rules but to the way they generate sounds) and I liked the result. Later I thought it wouldn’t work well, or it wouldn’t be interesting at all, but I implemented it anyways to see how it behaves. The idea just popped into my mind just as I was drifting into sleep one day. That said, the rules Otomata uses were derived without any type of experimentation whatsoever. So, if we take my past interest in these types of systems into account, it is an evolutionary step for me.

They are very simple to implement, use, and understand, yet they include almost all of the ingredients I care about. Working with cellular automata (CA) is like a recreational hobby for me. I’ve been programming my own tools to make art for many years and I don’t always work with very simple systems. They have clearly defined states, they use feedbacks (the system is fed back its previous state and generates a new state), they have well-defined rules, and as a result they have emergent behavior. I always found them fascinating for a multitude of reasons, the most important one being that they included the most essential elements I tend to employ for creating generative art. I have experimented with cellular-automata systems a lot in the past. Otomata originally was created as a browser based music app and has been adapted for iOS.īozkurt discussed his interest in cellular automata systems and generative art in an interview with disquiet: Go add some cells, change their orientation by clicking on them, and press play, experiment, have fun. This set of rules produces chaotic results in some settings, therefore you can end up with never repeating, gradually evolving sequences. If a cell encounters another cell on its way, it turns itself clockwise. If any cell encounters a wall, it triggers a pitched sound whose frequency is determined by the xy position of collision, and the cell reverses its direction. at each cycle, the cells move themselves in the direction of their internal states.

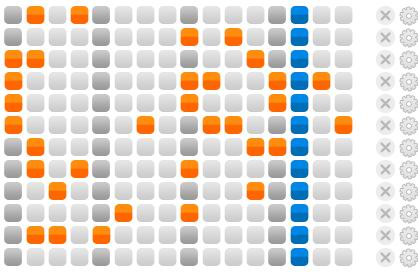

Otomata is also surprisingly deep, though, because it uses cellular automaton style logic:Įach alive cell has 4 states: Up, right, down, left. On one level, Otomata is a music toy – just press the buttons and something musically interesting emerges. It is best to have at least four neighbourhoods to be able to patch-program a great deal of complex patterns.Batuhan Bozkurt’s Otomata is a generative sound sequencer for iOS. This means neighbourhoods can be summed together for more complex signals or even the random output can be fed back in to be mixed with the CV.Įach neighbourhood needs a clock and a signal on the left or right input to get started, the cell gate outputs can then be used to activate cells in other neighbourhoods or even act as clocks for other neighbourhoods. There is also a CV input and inverted CV input with attenuator for each neighbourhood. Of course more than one cell may be alive at the same time so the resulting CV is far more complex than a standard 4 stage CV. As each cell lives it puts out a gate for the length of its lifetime and a voltage to a pot that can be attenuated and then summed to get a CV signal (and its inverse….and there is a staircase divider off the 4 cells to give a semi-random CV as well).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)